This detailed article will explore the multifaceted role of sugar in our diets, covering its various forms, metabolic pathways, health impacts, and practical strategies for managing its intake. The aim is to provide a comprehensive understanding for English-speaking readers.

Understanding Sugar in Diets

Sugar, a seemingly innocuous white crystalline substance, holds a complex and often controversial position in our modern diets. From the sweet indulgence of a dessert to its hidden presence in savoury snacks, sugar is ubiquitous. Yet, its pervasive nature belies a profound impact on our health, metabolism, and overall well-being. Understanding sugar in its various forms, how our bodies process it, and its implications for our health is paramount to making informed dietary choices and fostering a healthier lifestyle.

The Chemical Nature of Sugar

At its most fundamental level, sugar is a carbohydrate, one of the three macronutrients (along with fats and proteins) essential for human life. Carbohydrates are organic compounds composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms. Sugars are simple carbohydrates, or saccharides, categorized based on the number of sugar units they contain.

# Monosaccharides: The Simplest Sugars

Monosaccharides are the most basic units of sugar and cannot be further hydrolyzed into simpler forms. They are readily absorbed into the bloodstream.

# Glucose: The Body’s Primary Fuel

Glucose is the most abundant monosaccharide and serves as the primary source of energy for all body cells. It is the sugar that circulates in our blood and is directly utilized by the brain, muscles, and other organs for their functions. All other carbohydrates, whether simple or complex, are ultimately broken down into glucose for energy.

# Fructose: The Fruit Sugar

Fructose is a monosaccharide commonly found in fruits, some vegetables, and honey. It is also a key component of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), a widely used sweetener in processed foods. Fructose is metabolized primarily in the liver, and its excessive intake has been linked to various metabolic issues.

# Galactose: A Component of Milk Sugar

Galactose is another monosaccharide, less common in its free form but a vital constituent of lactose, the sugar found in milk and dairy products.

# Disaccharides: Two Sugar Units Combined

Disaccharides are formed when two monosaccharides are chemically bonded together. They must be broken down into their individual monosaccharide units before they can be absorbed.

# Sucrose: Table Sugar

Sucrose, commonly known as table sugar, is a disaccharide composed of one glucose molecule and one fructose molecule. It is derived from sugarcane or sugar beets and is the most common form of sugar added to foods and beverages.

# Lactose: Milk Sugar

Lactose is the disaccharide found in milk, consisting of one glucose molecule and one galactose molecule. Many individuals experience lactose intolerance due to a deficiency in the enzyme lactase, which is required to break down lactose.

# Maltose: Malt Sugar

Maltose is a disaccharide formed from two glucose molecules. It is produced during the malting process of grains, such as barley, and is found in malt beverages and some processed foods.

The Journey of Sugar: Digestion and Metabolism

Once consumed, sugars embark on a fascinating journey through our digestive system and into our cells, where they are transformed into energy or stored for future use.

# Digestion of Sugars

The digestion of sugars begins in the mouth with the enzyme salivary amylase, which starts breaking down complex carbohydrates. However, simple sugars like monosaccharides require little to no digestion and are quickly absorbed. Disaccharides are broken down into their constituent monosaccharides by specific enzymes in the small intestine, such as sucrase (for sucrose), lactase (for lactose), and maltase (for maltose).

# Absorption and Transport

Once broken down into monosaccharides, primarily glucose, fructose, and galactose, these sugars are absorbed through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream. Glucose is then transported to cells throughout the body, where it is used for immediate energy or converted into glycogen for storage.

# Glucose Metabolism: The Central Pathway

Glucose is the star of the show when it comes to energy production. It enters cells with the help of insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas. Inside the cells, glucose undergoes a series of metabolic pathways to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the body’s energy currency.

# Glycolysis: The Initial Breakdown

Glycolysis is the first step in glucose metabolism, occurring in the cytoplasm of cells. It breaks down glucose into pyruvate, releasing a small amount of ATP.

# The Krebs Cycle and Oxidative Phosphorylation

Pyruvate then enters the mitochondria, the cell’s powerhouses, where it is further processed in the Krebs cycle (also known as the citric acid cycle) and oxidative phosphorylation. These processes generate a significantly larger amount of ATP, providing the sustained energy needed for cellular functions.

# Glycogen Storage: Our Energy Reserves

When glucose intake exceeds immediate energy needs, the body converts excess glucose into glycogen, a complex carbohydrate stored primarily in the liver and muscles. Liver glycogen helps maintain stable blood sugar levels between meals, while muscle glycogen provides energy for physical activity.

# Fructose Metabolism: A Different Path

Fructose metabolism differs significantly from glucose metabolism. Unlike glucose, fructose is metabolized almost exclusively in the liver. While some fructose can be converted to glucose or lactate, a substantial portion is shunted towards lipogenesis (fat production), especially with high intake. This distinct metabolic pathway contributes to many of the adverse health effects associated with excessive fructose consumption.

The Health Impacts of Sugar Consumption

While sugar provides energy, its excessive and chronic consumption has been linked to a myriad of adverse health outcomes, making it a significant public health concern.

# Weight Gain and Obesity

One of the most evident consequences of high sugar intake is weight gain and obesity. Sugary drinks, in particular, contribute to excess calorie intake without promoting satiety. The rapid rise in blood sugar and subsequent insulin spike can also lead to increased fat storage, especially visceral fat around the organs.

# Type 2 Diabetes

Chronic overconsumption of sugar, particularly refined sugars and sugary beverages, is a major risk factor for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Constant high blood sugar levels strain the pancreas, leading to reduced insulin sensitivity over time.

# Cardiovascular Disease

Research increasingly points to sugar as a significant contributor to cardiovascular disease, independent of its role in obesity. High sugar intake can lead to elevated triglycerides, lower “good” HDL cholesterol, increased “bad” LDL cholesterol, and higher blood pressure, all risk factors for heart disease.

# Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

As fructose is primarily metabolized in the liver, excessive fructose consumption can lead to the accumulation of fat in liver cells, resulting in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD can progress to more severe liver conditions, including cirrhosis and liver failure.

# Dental Caries

Sugar provides a readily available food source for bacteria in the mouth. These bacteria produce acids that erode tooth enamel, leading to cavities and dental caries.

# Mood and Energy Swings

While sugar provides a quick energy boost, it is often followed by a “sugar crash” as blood sugar levels rapidly decline. This can lead to fatigue, irritability, difficulty concentrating, and mood swings, contributing to a rollercoaster of energy levels throughout the day.

# Inflammatory Responses

High sugar intake can promote chronic low-grade inflammation throughout the body. Chronic inflammation is a driver of numerous chronic diseases, including heart disease, arthritis, and certain cancers.

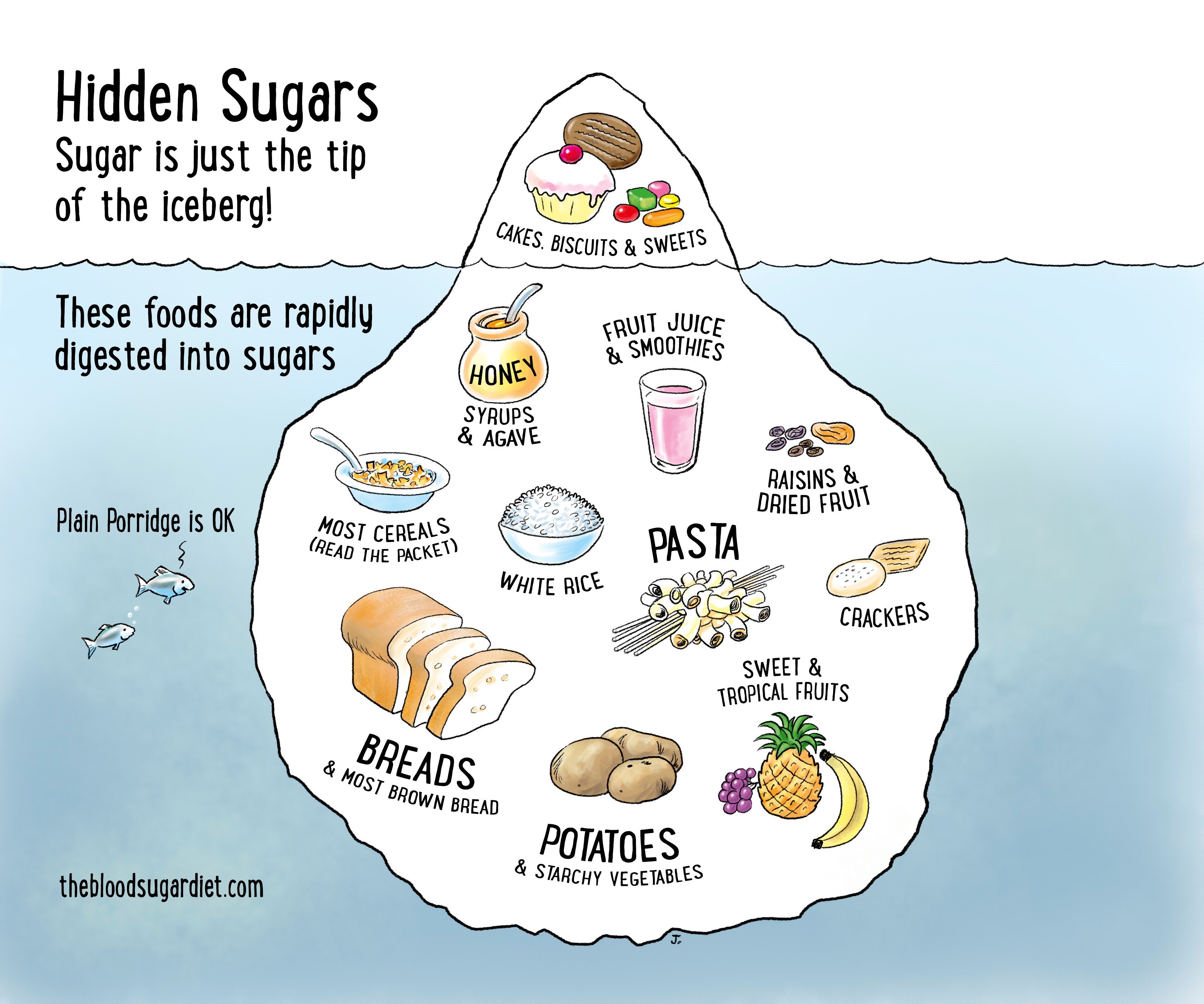

Hidden Sugars and Reading Labels

One of the greatest challenges in managing sugar intake is the pervasive presence of “hidden sugars” in processed foods. Manufacturers often add various forms of sugar to enhance flavor, extend shelf life, and improve texture, often under deceptive names.

# Common Names for Added Sugars

To avoid being misled, it’s crucial to be aware of the many names sugar can hide under on food labels. These include:

# High-Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS)

A common sweetener made from corn starch, HFCS is prevalent in soft drinks, baked goods, and many processed foods.

# Corn Syrup Solids

Another form of corn-derived sugar, often used in powdered products and some dairy items.

# Dextrose

A simple sugar chemically identical to glucose, often found in sports drinks and processed snacks.

# Maltodextrin

A complex carbohydrate that is rapidly digested into glucose, often used as a filler or thickener in processed foods.

# Brown Rice Syrup

A sweetener made from rice, often marketed as a healthier alternative but still a source of added sugar.

# Agave Nectar

A syrup extracted from the agave plant, primarily composed of fructose, and often perceived as a healthier option despite its high fructose content.

# Evaporated Cane Juice

Essentially another term for sugar, implying it is less processed than refined white sugar.

# Fruit Juice Concentrate

While derived from fruit, fruit juice concentrate is a highly processed form of sugar with most of the fiber removed, leading to a rapid blood sugar spike.

# Decoding Food Labels

When reading food labels, always check the “Ingredients” list. Ingredients are listed in descending order by weight, so if sugar or any of its aliases appear near the top of the list, the product is likely high in added sugar. Pay attention to the “Added Sugars” line under the “Nutrition Facts” panel, which provides a specific quantity in grams and as a percentage of the daily value.

Strategies for Reducing Sugar Intake

Reducing sugar intake can be a challenging but highly rewarding endeavor. It involves making conscious choices, adopting healthier habits, and understanding how to navigate the modern food environment.

# Prioritize Whole, Unprocessed Foods

The most effective strategy is to build your diet around whole, unprocessed foods. Fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, whole grains, and healthy fats are naturally low in added sugars and provide essential nutrients and fiber.

# Limit Sugary Beverages

Soft drinks, fruit juices, sweetened teas, and energy drinks are major contributors to added sugar intake. Opt for water, unsweetened tea, or coffee instead. If you crave flavor, infuse water with fruits or herbs.

# Be Mindful of Breakfast Cereals

Many breakfast cereals are loaded with sugar. Choose plain oats, whole-grain cereals with minimal added sugar, or prepare your own healthy breakfasts like eggs or Greek yogurt with berries.

# Choose Plain Dairy Products

Flavoured yogurts and milk often contain significant amounts of added sugar. Opt for plain yogurt and unsweetened milk, and add your own fresh fruit or a touch of natural sweetener if desired.

# Read Food Labels Diligently

Make it a habit to read nutrition labels and ingredient lists. Compare products and choose those with the lowest amount of added sugars.

# Cook More at Home

Preparing meals at home gives you complete control over the ingredients, including the amount of sugar. Experiment with natural sweeteners like small amounts of honey, maple syrup, or stevia, but use them sparingly.

# Beware of “Low-Fat” Products

Often, when fat is removed from a food product, sugar is added to compensate for flavor and texture. Don’t assume “low-fat” means healthy; always check the sugar content.

# Gradually Reduce Sweetness

If you’re accustomed to very sweet foods, gradually reduce the amount of sugar you add to drinks or recipes. Your taste buds will adapt over time, and you’ll begin to appreciate more subtle flavors.

# Choose Whole Fruits Over Juices

While fruit is healthy, whole fruit provides fiber that slows sugar absorption. Fruit juice, even 100% juice, removes much of this fiber, leading to a quicker blood sugar spike.

# Manage Cravings

Sugar cravings are common, but they can be managed. Ensure you’re eating balanced meals with adequate protein and fiber to promote satiety. If a craving strikes, try a healthier alternative like a piece of fruit, a handful of nuts, or a glass of water.

# Be Patient and Persistent

Reducing sugar intake is a journey, not a destination. There will be slip-ups, but consistency and perseverance are key. Celebrate small victories and focus on long-term sustainable changes.

The Role of Artificial Sweeteners

Artificial sweeteners, or non-nutritive sweeteners, offer sweetness without the calories of sugar. They are widely used in diet drinks and “sugar-free” products.

# Common Artificial Sweeteners

Aspartame: Found in many diet sodas and sugar-free chewing gum.

# Health Considerations of Artificial Sweeteners

While artificial sweeteners can help reduce calorie and sugar intake, their long-term health effects are still a subject of ongoing research and debate. Some studies suggest potential impacts on gut microbiome, glucose metabolism, and even appetite regulation. It’s advisable to use them in moderation and to prioritize whole, unprocessed foods.

Conclusion

Understanding sugar in our diets is a critical step towards achieving optimal health. From its basic chemical structure to its intricate metabolic pathways, and its far-reaching health consequences, sugar’s influence is undeniable. By becoming informed consumers, diligently reading food labels, and making conscious choices to reduce added sugar intake, we can empower ourselves to take control of our health and embark on a path towards a more balanced and vibrant life. It’s not about eliminating all sugar, which is unrealistic and unnecessary, but rather about recognizing its pervasive presence, minimizing its added forms, and appreciating the natural sweetness of whole foods. The journey to a lower-sugar diet is a journey of awareness, intention, and ultimately, improved well-being.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/EW-Meal-Plans-Healthy-Weight-Gain-Day-4-1x1-alt-81577102cff74485ac146541976d8b22.jpg?resize=200,135&ssl=1)